Clara Gerhardt, MBA, PhD. Samford University

“If we lived simply, others can simply live.”

Jenny and Jason Waltman, Cofounders of Grace Klein Community

Introduction

If bread is the staff of life, then sharing nutrition with others is exponentially powerful. As a Practicum supervisor I have experienced the other side of a local charitable community that focuses on food distribution to the needy. I see the powerful effect of being part of the cycle of service; how the hearts of those who share are impacted by the power of the gesture, and how it creates a life of its own by giving forward. Generosity touches on the foundational principle of sharing our bread, and thereby sharing our hearts. Our students are learning about the power of giving, serving, and making a difference. A priceless life lesson is best learned in a practical setting such as community distributing food.

Each initiative is amplified when communities collaborate; when they reach out across obstacles to find partners with likeminded ideals. This addresses so much more than the microsystemic challenge of a family dealing with hardship. Successful projects are collaborative by nature because they form bridges between participating parties to address multifaceted problems with macrosystemic implications. It means reaching out to communities in under-resourced neighborhoods, which includes rural settings. Ideally initiatives address societal responsibility, community building, empowerment, stewardship of resources with an eye on sustainability, future needs and more.

According to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, the complexity of our existence rests upon foundational needs for nourishment, safety, and shelter. If any of these are under threat, the effects spill over into related areas of functioning. A variety of growth needs may be affected, even sacrificed, because the focus shifts to deficiency needs (Noltemeyer et al., 2021). Food insecurity is an example of the challenges faced by those in poverty or a variety of crises affecting families.

Outline of initiatives

Attempts have been made to address food insecurity at various systemic levels, ranging from macro- through to microsystemic levels.

- Governmental interventions: focusing on those in need through food stamps, subsidies, welfare, and the like.

- Local council and county initiatives: repurposing space in underserved areas for nonprofit grocery stores.

- Legislative interventions: such as initiatives minimizing food waste in the hospitality and food industries through redistribution of safe and edible food.

- Indemnity reduction: legislative protection for redistribution of safe and edible food without major risks of litigation.

- Nonprofit initiatives: providing community support, e.g., food banks, food redistribution centers, and education on wise stewardship, resourcefulness, reallocation of resources, money management, nutrition, food preservation and gardening. May be supported with grants and tax benefits.

Policies pertaining to food insecurity

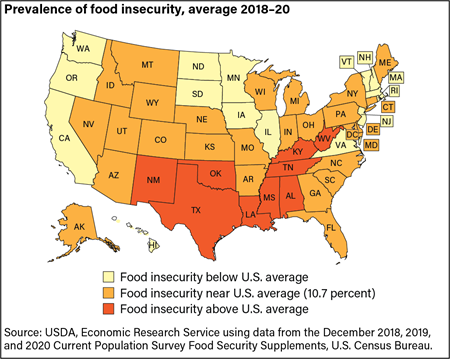

Food insecurity is loosely defined as a situation in which individuals do not have reliable access to safe, nutritious food in quantities that meet their caloric needs. In the state of Alabama, which includes rural Alabama, a 2021 estimate is that one out of five children face food insecurity and hunger, and that the prevalence of household food insecurity tends to be above the U.S. average. According to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) in 2021, about 10.2% of U.S. households faced ongoing and persistent threats of significant food insecurity, while another almost 4% of households had low food security. Importantly each household affects multiple children, translating to a quarter or 25% of growing children. The report states that between 2020 and 2021, food insecurity increased in households without children, especially where women lived alone. Food insecurity also affects the elderly; “Senior Hunger” and is more pronounced for elders living alone. The percentages are even larger when intermittent and occasional food insecurity are considered. These children depend on a balanced diet to meet developmental needs ( https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/ and https://www.feedingamerica.org/hunger-in-america ).

The prevalence of food insecurity reaches across geographical areas. The U.S. Dept of Agriculture: Household food security in the United States in 2021 (published 2022) differentiates areas of residence as living within larger metropolitan areas and principal cities, as opposed to living outside metropolitan areas and principal cities. The distribution between the urban and rural groups was roughly similar, with the metropolitan areas and principal cities tipping the distribution slightly in their favor, meaning displaying slightly greater prevalence of food insecurity (Coleman-Jensen et al., 2022, p.20).

Limited food accessibility, often termed a “food desert,” can be addressed with the creation of nonprofit grocery stores, pop-up food distributions, or community refrigerators. The incentives are humanitarian, rather than financial, and these tasks are typically undertaken by charitable and community-oriented organizations to contribute to the betterment of all. Dealing with these challenges “… needs systemic change…everything from a higher minimum wage or better public transit that would make food more accessible” (Ahmed, 2022).

The State of California introduced various initiatives addressing food waste. In 2020 about 23% of the Californian population had insufficient food to eat and displayed food insecurity. One angle of attack is keeping compostable food out of landfills. Individuals and businesses need to manage household waste responsibly. The consumer of food should be included if we attempt an integrated approach. Educational initiatives that address the consumer are important: family food preparation, taking responsibility for nutritional food choices, and avoiding waste within family kitchens, are some entry points in addressing the complexity of food insecurity. Just as the country must learn to address food waste, the consumer must consider how they are wasting food. If change starts with the proverbial “me” it is more sustainable.

A second allied approach deals with food recovery. Senate bill 1383 requires that by 2025 California will recover 20% of edible food to safely feed people in need. The food rescue or food recovery initiative also keeps the food out of landfills. A trickle-down effect of this legislation requires the establishment of food recovery programs and the strengthening of existing ones. Donors are responsible for recovering as much of the edible food as possible to prevent unnecessary waste. Food recovery organizations and services must document their participation in programs pertaining to Senate bill 1383. Donors commented on how transportation costs can be an obstacle. Nevertheless, each meal, feeding a hungry mouth, contributes to the greater good on many levels. California Recycle estimated significant reduction in the carbon footprint, while creating employment opportunities. In a three-year period since 2018, these programs have been able to repurpose 86 million meals in California. (https://calrecycle.ca.gov/organics/slcp/foodrecovery/).

These large-scale initiatives require donor organizations be matched with distributing networks and food banks. Supporting materials can include guides to safe surplus-food handling to setting up partnerships and guidance concerning tax benefits and grants. The food rescue initiative must be addressed at several entry-points and has the potential of positively affecting the community on several levels.

[Diagram: Prevalence of food insecurity in the U.S.]

Case Study

The following case study describes a local initiative, Grace Klein Community, in Alabama (https://gracekleincommunity.com/). A grassroots effort started by citizens Jason and Jenny Waltman, as a nonprofit enterprise in April 2010, recovered and distributed over one million pounds (about 454,000 kg) of food in 2021 responding to food insecurity in 40 of 67 Alabama counties, many of these affecting rural areas. Several Human Development and Family Science students at Samford University have completed practicum experiences in this setting. They learn about the systemic effects of food redistribution, the economic challenges for recipients as well as for the distributor as a nonprofit organization. There is complexity in maintaining such a large-scale initiative, especially as this food bank deals with perishable food items as well, and the time frame for collecting and subsequent redistribution can affect food safety. The food is received and redistributed within twenty-four hours.

The intent of such an initiative is manifold. On the one hand, food rescue prevents large scale waste affecting environmental concerns, by making it feasible to donate left over and excessive food. In many areas the tendency is to dispose of usable food through the waste system as opposed to taking a longer-term responsibility and asking, where does this food cycle continue and with what outcomes? The reasons for food disposal and waste are many; fear of being sued for providing food not considered the “best by date” or freshness, interpretation by consumers of food being unsafe due to lack of education, the cost of delivery and the labor entailed to redistribute. In short, the effort of implementing sustainable solutions may be more challenging than taking the short-term route reflecting short range vision and creating more waste.

Grace Klein Community goes beyond addressing food waste and focuses on edible food distribution and composting. Their vision is to share resources, and in that manner build relationships “to ignite restoration of individuals, families, and communities” (https://gracekleincommunity.com/). Its mission is encapsulated in the phrase:

“Love. Serve. Share. Repeat.” meet physical and spiritual needs both locally and globally.

Student reflection

As practicum supervisor, I have asked my students: “What skills, insights are you gathering from this experience?” The following reflection was written by an intern:

“I have loved working at Grace Klein Community. My supervisor has been such an amazing part of this practicum. Something she said recently that I thought was pivotal, was “if we lived simply, others can simply live.” The idea of living simply allows one to help others who need basics; to meet their needs, which may be greater than simply the need for food.”

Families need community to thrive. Community is built through the sharing of resources pertaining to families. Our students learned to be part of these greater families. They were able to adopt the values epitomized by Grace Klein, namely to:

- Embrace community by building valued relationships

- Compassionate interactions by caring deeply

- Respect and honoring diversity

- Teamwork by focusing on a common vision

- Stewardship of gifts, while inspiring resourcefulness

The combined standards and goals of Grace Klein Community inspire opportunities to exemplify the values required to build character. They are also the building blocks for greater resilience; the process from which communities are strengthened: one food basket at a time.

References

Ahmed, Amal (2022). Our unequal earth. Market with a mission: Non-profit grocery stores help heal ‘food deserts. The Guardian, 3 April. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/apr/03/non-profit-grocery-store-food-desert-texas

Coleman-Jensen A. ,Rabbitt M.P., Gregory, C.A. & Singh, A. (2022). USDA: U.S. Dept of Agriculture: Household food security in the United States in 2021. A report summary of the economic research service. September 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details?pubid=104655

Feeding America. https://www.feedingamerica.org/hunger-in-america

Grace Klein Community, retrieved from https://gracekleincommunity.com/

Noltemeyer, A., James, A. G., Bush, K., Bergen, D., Barrios, V., & Patton, J. (2021). The relationship between deficiency needs and growth needs: The continuing investigation of Maslow’s theory. Child & Youth Services, 42(1), 24-42.

Acknowledgment

The author gratefully acknowledges the support of Grace Klein Community in offering meaningful practicum opportunities to students in Human Development and Family Science.

About the author. Dr. Clara Gerhardt is a clinical psychologist. She is a Distinguished Professor at Samford University, in Birmingham, Alabama.

This article may also be found in the book linked here: https://www.routledge.com/Local-Government-Administration-in-Small-Town-America/Clinger-Handley-Eaton/p/book/9781032263281